Wayne State student seeks to treat Indigenous adolescents with PTSD using art therapy

Studies show Indigenous people experience disproportionately higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), addiction, and suicide than the general U.S. population, said Alexis Estes, a trend exacerbated by intergenerational trauma and unresolved grief passed down through epigenetics.

A master’s student in art therapy at the Wayne State University College of Education, Estes is paternal Lakotan and a member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. For months, she’s been in Chamberlain, SD, on the Lower Brule Sioux Reservation writing a literature review on the benefits of art therapy for Indigenous adolescents and laying the groundwork for her own research study in Lower Brule High School.

Estes will present her research and plans for her study at the 2025 Graduate Research Symposium on Feb. 26 at the Wayne State University Student Center.

Unresolved trauma

Estes grew up in Haslett near East Lansing. She chose Wayne State University to remain close to family, for its art therapy program—an emerging discipline that isn’t recognized by a number of states, including South Dakota—and its diverse campus population.

“It really appealed to me as someone researching native populations to explore the field of art therapy through a multicultural lens, to learn how it’s compatible in working with different populations.”

The plan, however, has always been to take back what she learns to the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe. Estes’ Lakotan father and mother of Russian descent met in Chamberlain, but it was her father who raised her, and she always felt a pull to return to the place he fought so hard to escape.

“My dad is a boarding school survivor,” Estes said. “He was forcibly taken from his parents on the reservation in Lower Brule and taken stateside where he was placed in St. Joseph’s Indian School.”

The U.S. Indian Boarding School policy saw hundreds of thousands of Native American children removed from their homes between 1816 and the 1960s and placed in boarding schools operated by the federal government and churches in an effort to assimilate the children into Western society by stripping them of their language and culture, Estes said.

“The St. Joseph’s Indian School is still operational today. How it operates has changed, but its legacy and other institutions’ like it live on in the great loss of identity of the Native American people. The byproduct is the increased mental health disparities in our communities.”

The art of healing

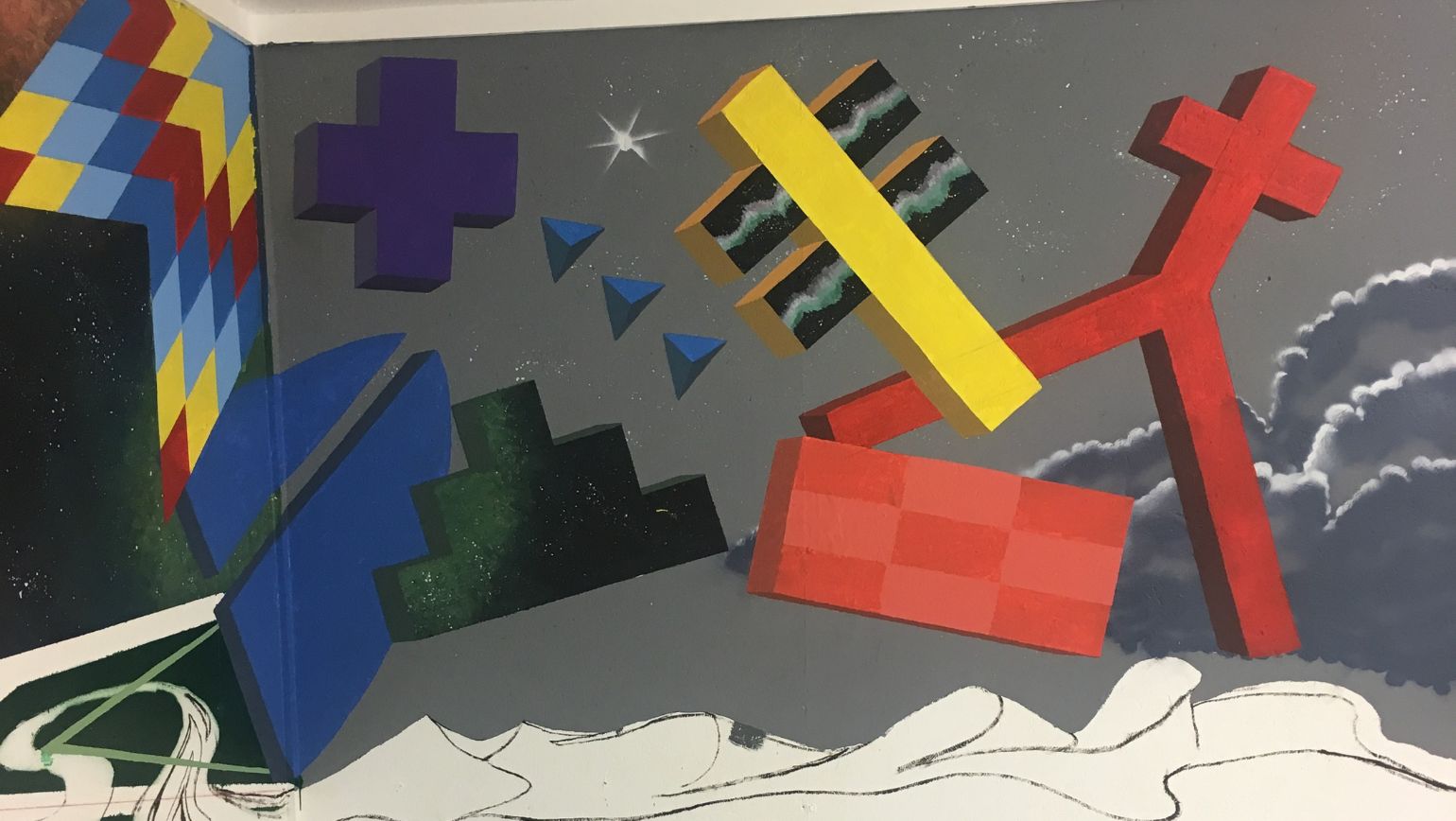

Estes has found her own peace in art. She has painted murals in the West Brule Recreation Center on the Lower Brule Sioux Reservation; at the Nativo Lodge Hotel in Albuquerque, NM; at Tati Ortiz’s pottery art gallery in Mata Ortiz, Mexico; and at the Women of Nations women’s shelter in St. Paul, MN. Each one depicts abstractions of animals and landscapes, beadwork symbols, and night skies with constellations.

It’s a kind of therapy she is eager to employ at Lower Brule High School once her research request is approved by the Wayne State Institutional Review Board. She plans to create an after-school program wherein two groups of five student volunteers will work together painting a mural of a medicine wheel over a span of seven weeks.

The medicine wheel is a sacred symbol and teaching tool in Indigenous tribes that represents one’s connections to all things in the universe, Estes said.

“The students will decide what symbols to paint in their murals using the prompt, 'How do you care for your mental health?' The symbols will depict what the students choose represents caring for their mental health. There are seven directions in the medicine wheel, so we will talk about a different direction at the start of each group art therapy session.

“Uniting Indigenous methodologies of knowledge sharing, such as storytelling and group mural painting, will help these groups to identify the impact of historical oppression on their mental health, to strengthen their sense of identity, to improve their self-awareness, and to create a sense of a strong Tiospaye (extended-family).”

Estes said the purpose of the endeavor is twofold: to provide Indigenous adolescents with a creative outlet in a path toward healing, but also to educate teachers and other professionals so they might better serve the youth in Native American communities.