Wayne State graduate student analyzes The New York Times’ coverage of Instagram’s ‘It girl’

Social media is with us everywhere we go. At the single tap of an app, we have access to a trove of glitzy content posted by glamorous strangers that can, well, leave us feeling a little envious. Current research shows that teenage girls and young women experience the most adverse side effects to their mental health when it comes to spending time online.

It got Alexandra Porter thinking about how journalistic reporting informs the women user experience on these private platforms.

A Ph.D. student in communication at Wayne State University, Porter has a background in communication design and brand identity.

“I came into my graduate program wanting to understand the philosophical underpinnings of developing messages and aesthetics in media,” she said.

What better way to do that than conducting a critical analysis of global news giant The New York Times’ coverage of Instagram? Arguably the most “aesthetically” driven social app, Instagram is America’s third most popularly used platform behind Facebook and YouTube. About half of Americans use Instagram, 56 percent of them girls and women.

Experts agree that gender is a socially constructed phenomenon deeply rooted in dominance and constraint to the detriment of women, Porter said. How people operate in society is largely determined by gender dynamics, and that filters into online spaces.

“I wanted to figure out how NYT reported in its technology section on Instagram and constructed this ideal woman user that coincides with cultural norms present in the U.S.,” Porter said.

Under the advisement of faculty mentor Stine Eckert, Ph.D., Porter drew from 10 years of NYT articles and supplemental images published between 2012 and 2022.

Porter presented her findings at the 2024 Graduate Research Symposium in February.

Constructing the ‘It girl’

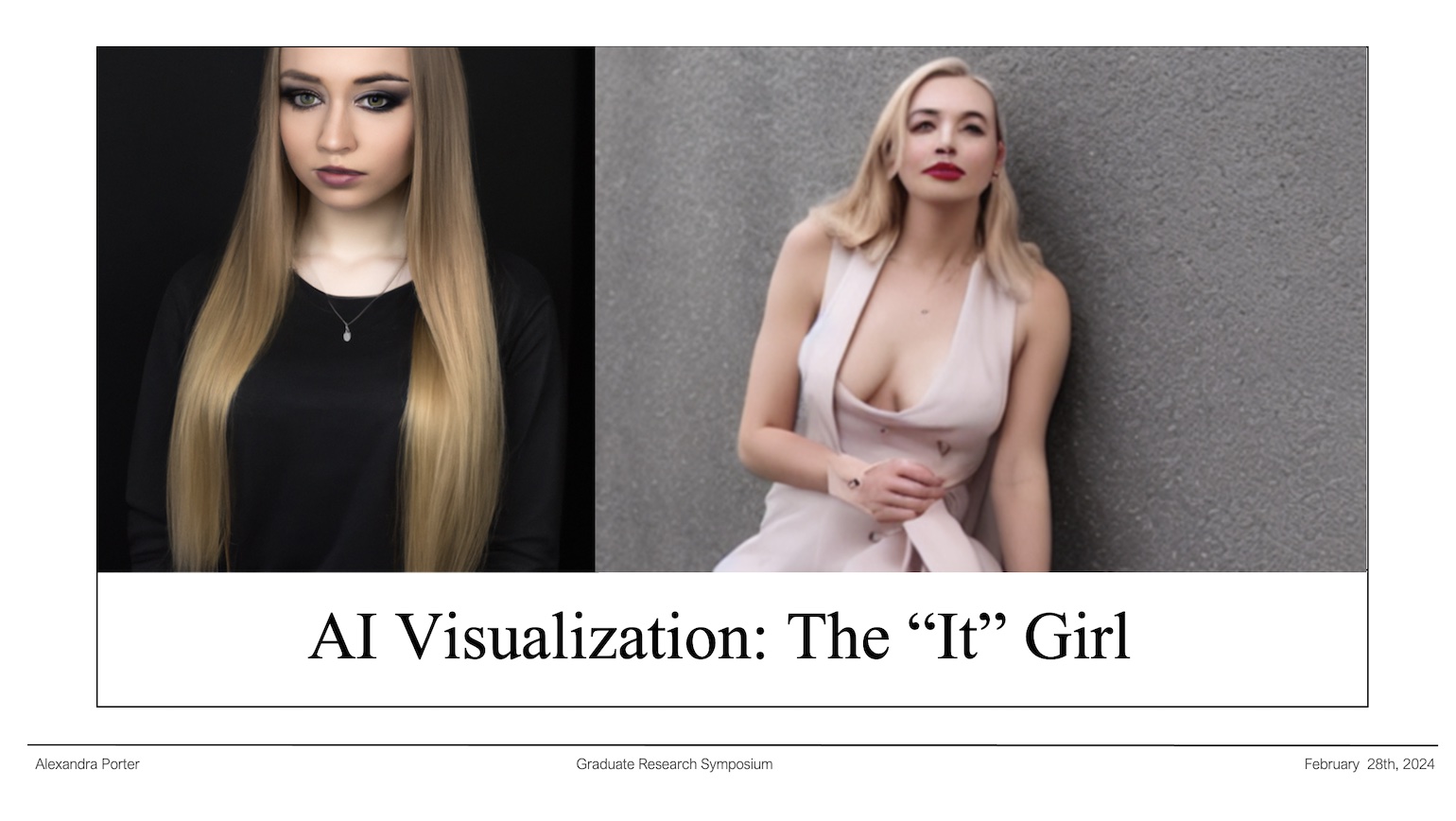

The NYT favored a particular type of woman in its Instagram coverage that Porter calls the ‘It girl.’ Go-getter influencers and business-savvy entrepreneurs who managed to tap into the algorithm of how to be successful online. The coverage sells this lofty ideal and posits that it’s a personal problem for those unable to attain it.

It was through the 144 supplemental images that Porter unsurprisingly discovered that this ideal is also often young and white, thin but curvy with a short skirt and plunging neckline, blonde with blue eyes. Not indicative of a platform with a global audience.

“There is very much this post-feminist ideology that the public has triumphed over sexism and we’re now in the new age of individual liberation,” Porter said. “I can see it in the NYT coverage as well as the content that tends to perform better online.”

One of the problems with this post-feminist narrative, she said, is that when harassment against women occurs online, it’s framed as a singular, one-off problem instead of part of a systemic one. Block and move on, as they say. You can report a user or post, but these efforts often have mixed results. That’s because moderators responsible for removing content operate within their own mixed bag of biases and selectively-enforced guidelines, Porter said.

Community coded

In addition to a decade’s worth of NYT coverage, Porter scanned every iteration of Instagram Community Guidelines published between 2012 and 2022.

“I saw a theme of performative allyship regarding rules and language on gender, meaning they were including considerations about women and their bodies but only on a surface level.”

In 2012, Instagram set broad terms on permissible content with an emphasis of “keeping your clothes on,” Porter said. “Nudity was applied to all genders but moderation of photos often only applied to pictures of women.” A common occurrence demonstrated by the hashtag #FreeTheNipple.

Then in 2016, Instagram added the language “some photos of female nipples [are allowed],” including photos of post-mastectomy scarring and women actively breastfeeding.

The guidelines remained relatively unchanged on gender and nudity between 2016 and 2022, Porter said, despite the emergence of the #MeToo movement and ongoing reports from female Instagram users about the surveillance and removal of their content without clearly defined reasons provided by moderators. Most of these complaints came from women who did not fit that stereotypical mold of an ‘It girl,’ Porter said.

In 2022, the guidelines provided more context on when photos depicting female nipples are allowed, including birth-related moments and health-related situations, such as gender-confirmation surgery, and acts of protest. But ultimately, the decision about what does and does not get removed is up to individual moderators.

Porter added that anytime binary language is used to moderate content, it leaves non-binary and transgender users to navigate an already confusing landscape.

Disrupting the feedback loop

“I didn’t go into this with the ultimate goal of tearing down The New York Times or advocating for users to swear off social media,” Porter said. “It’s not feasible, social media is going nowhere, and there are countless positive things we derive from it. I also don’t think NYT authors are publishing these things with malicious intent. They’re just people out here navigating the same social norms we all are.”

She said the goal of her research is to showcase the various ways we buy into ideologies that aren’t disseminated with our best interests in mind as well as the challenges reporters and moderators face when navigating these issues. Her hope is that one day she can inspire alternatives that disrupt the way we have come to use social media; creating platforms that contribute to, not detract from our well-being.

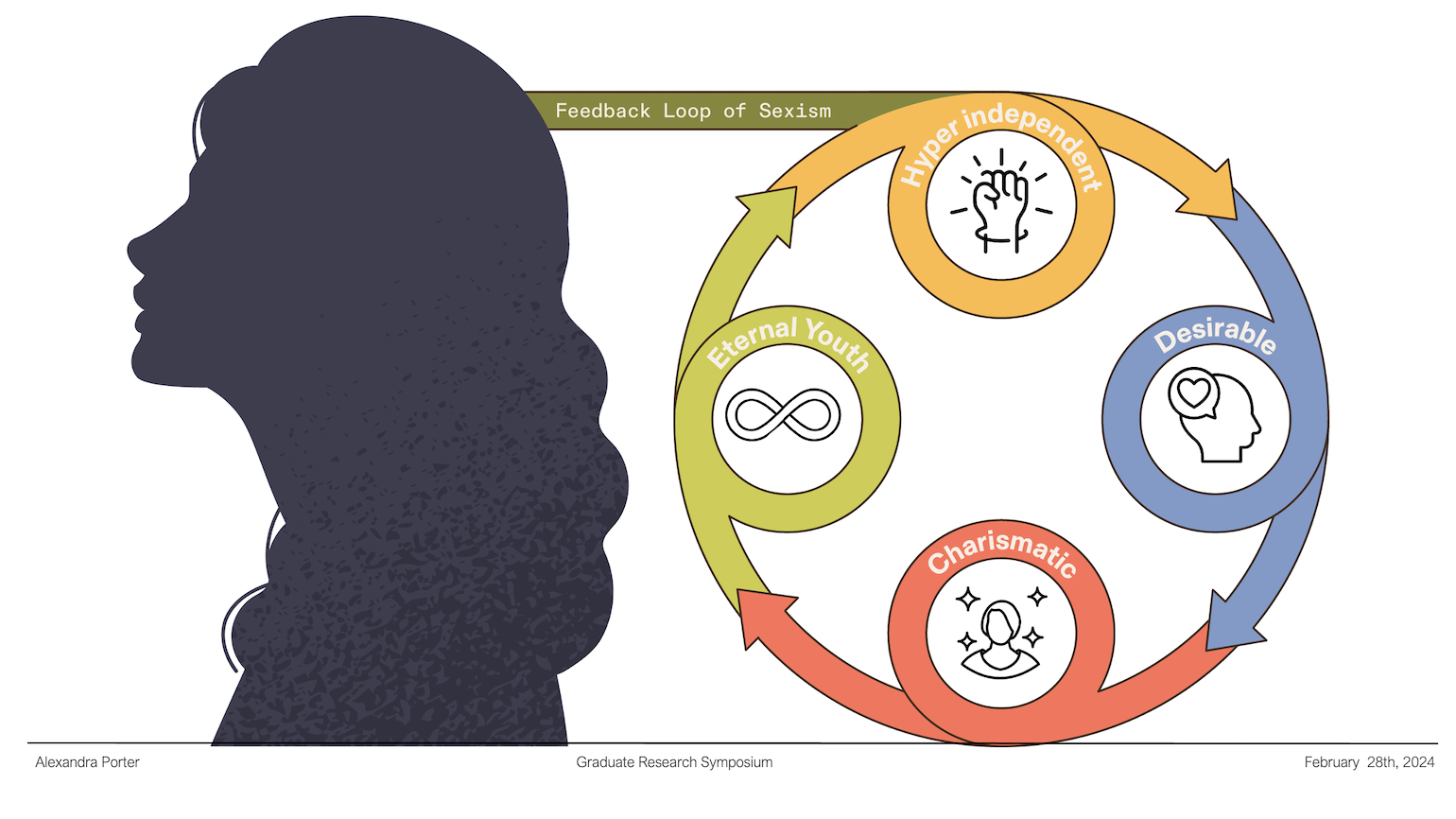

“Just be intentional about how you exist and what you consume online. There exists this feedback loop of sexism that fixates on enthusiastic and hyper-independent women as being these desirable commodities that denies every single one of us equitable social capital. It can make you crazy because you start to internalize these pressures you have no control over creating.”

By Kristy Case