The ‘Obama effect’: Research explores how Black women internalize and conceptualize beauty standards

A common proverb says ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder,’ but research tells us beauty standards have by and large been set by the white upper class. Black women have a long history of molding their beauty regimen to fit the eurocentric status quo, from straightening their hair and using lightening creams to settling for pale and pink cosmetics when the beauty industry fails to provide products for darker skin tones.

Kearabetswe Mokoene, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Sociology, explores how women of color internalize and conceptualize beauty standards that disqualify their natural aesthetics. She recently presented her project “The ‘Obama effect’: Young Black women’s conceptualizations of beauty” at the annual Graduate Research Symposium. Her findings are derived from 10 interviews she conducted with college-educated Black women, ages 18 to 35, in the Detroit metropolitan area.

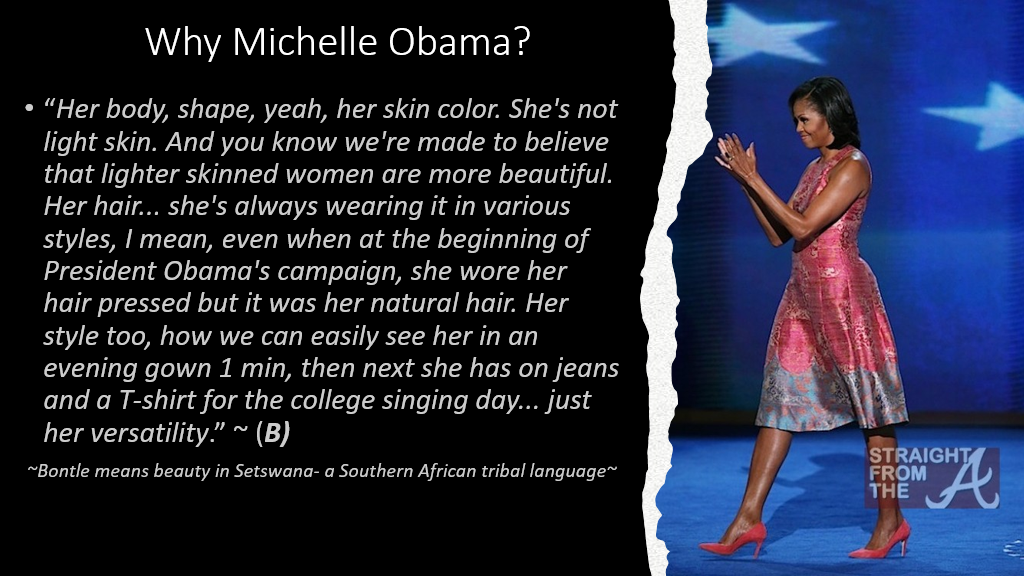

When she asked who embodies beauty to them, each one answered former First Lady Michelle Obama.

“Mrs. Obama’s rise to social prominence coincided with these young women’s formative years, which inevitably influenced much of their overall socialization, including beauty socialization,” Mokoene said. “Mrs. Obama was all they heard about, from the mainstream media, their mothers, their communities. I think when one sees a reflection of themselves in such authoritative spaces, they are bound to see beauty and perfection.”

In the U.S., it doesn’t get more authoritative than the White House.

Beauty goes well beyond looks, Mokoene said. A number of respondents lauded Obama’s confidence. Known for her motto “When they go low, I go high,” Obama experienced a barrage of personal insults throughout her husband President Barack Obama’s campaign and presidency. Mokoene thinks how Obama handled her trolls had a significant impact on young Black women.

But even Obama was strategic about the hairstyles she chose while at the White House. She told The Washington Post in 2022 she did not want her natural hair overshadowing her husband’s political goals.

A sentiment the women Mokoene interviewed understand. When she asked interviewees to place physical attributes such as skin, hair, and body in a hierarchy of importance, every single one put hair first.

“Some of these women have vivid memories of going to salons with their mothers or having some level of hair regimen starting from the tender age of three. Memories of hearing about the importance of having great hair from their female primary socializing agents, such as mothers, grandmothers and aunts.”

Socialized beauty standards

A South African citizen who grew up amid apartheid—legislation that upheld segregation against non-white citizens until the 1990s—Mokoene is no stranger to the expectations of conformity.

"I have early memories during my formative years of my skin tone being a constant point of comparison to my peers who had lighter skin shades. In their defense, it was the norm. That's when I started to realize that there's something wrong with being dark. It's impossible not to internalize such things, especially when you are just starting your teens."

In South Africa, the beauty hierarchy prioritizes skin tone above hair and other eurocentric aesthetics. Many Black girls' introduction to racial beauty standards are not with hair relaxers but skin lighteners with depigmenting agents of which South Africa has a complex history.

Conducting research has provided an opportunity for Mokoene to unpack her own childhood.

“The nuances of language begin early on in the home.” From songs on the radio to fussy relatives and cosmetic advertisements, Mokoene can’t remember a time she was not incessantly reminded of her skin.

A number of the women she interviewed reported something similar: their obsession with hair began at home when mothers and grandmothers looked at textured hair as something to be fixed instead of celebrated. It was ingrained within them early on that conformity is a must for career success. For social acceptance. For survival.

Future research

Mokoene’s work presented at the GRS is a subset of a larger study for her dissertation that will explore how Black women across age and social class conceptualize beauty. She hopes her research helps change how women of color think about themselves in the beauty strata.

She is optimistic about the future.

“Conversations are ongoing about normalizing and celebrating natural aesthetics in all its forms. Admittedly we have a long way to go, but progress has also been made to this end. The beauty industry is catching on, and I’m impressed to see many young Black women and women of color in the U.S. coming up with beauty products for people who look just like them.”