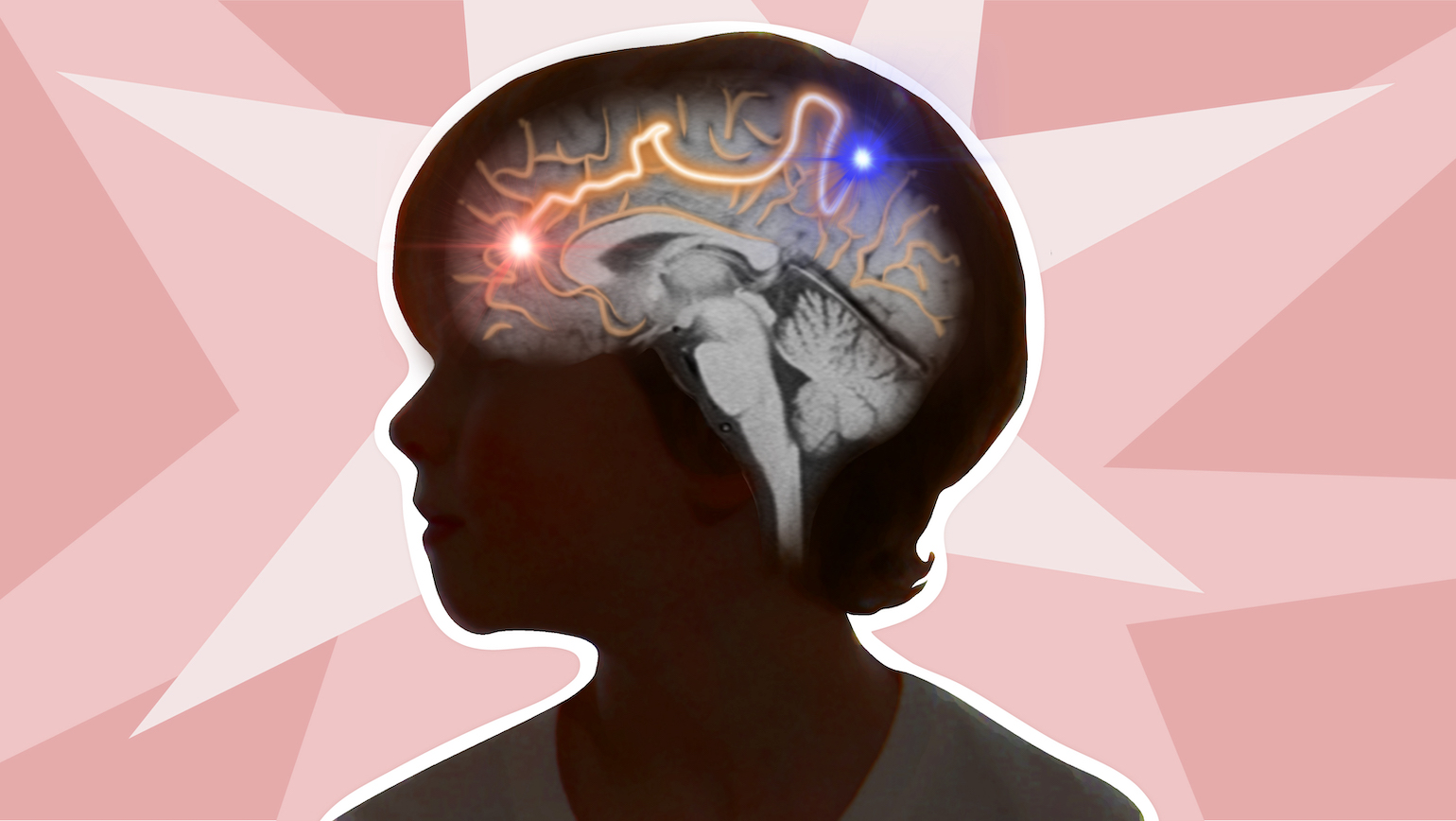

Understanding how pediatric epileptic spasms move through the brain

Epileptic spasms are one of the most prevalent forms of seizures experienced by infants and young children. Unfortunately, they’re also one of the most difficult to treat, says Nolan O’Hara, an MD/PhD student in the Wayne State University School of Medicine.

Currently completing medical clerkships in the Detroit Medical Center, O’Hara studies young patients whose seizures did not respond to anti-epilepsy drugs and have turned to neurosurgery for treatment.

“Patients undergo a pre-surgical workup that includes MRI of the brain and scalp-electrode recordings during their seizures, giving physicians a rough idea of where the seizures might be coming from,” he says. The skull is opened and electrodes are placed again, this time directly on the brain where seizure origin is suspected. The patient is monitored until seizures occur. “A second surgery is then done to remove the brain tissue that is determined to be seizure-generating.”

Nearly two-thirds of patients who qualify for surgery come out of the procedure seizure-free, he says, and can discontinue anti-epilepsy drugs, which can have significant cognitive side effects for young patients who are at a critical period of brain development.

It's a different story for those who experience epileptic spasms.

“Epileptic spasms spread across the brain so quickly that it can be hard to determine surgical targets, and if there is no obvious brain lesion on MRI or other imaging to guide surgery, about half of patients may still not achieve total post-surgical seizure freedom," he says. "Difficulties localizing a precise surgical target also means that larger areas of brain tissue will likely be removed, which can increase risk for complications and developmental deficits.”

Mapping epileptic spasms

O’Hara and other neuroscientists at Wayne State recently took a retrospective look at surgical brain recordings of young patients between the ages of 1 and 11 experiencing epileptic spasms and compared them using diffusion MRI tractography—an imaging technique that characterizes the communication structures of the brain.

The procedure is analogous with constructing a "roadmap" of patients' structural brain pathways using diffusion MRI, he says. Brain recordings of patients experiencing epileptic spasms were overlaid with MRI and the "traffic" of seizure activity recorded at the brains' surface to determine the origions of seizure activity.

“On average, the timing of seizure activity spread aligned with features of direct corticocortical white matter pathways through the brain, suggesting that seizure activity is propagating through an identifiable brain network. We also found that patients who did not respond as well to surgery showed faster seizure spread along these pathways, suggesting that analyzing seizure spread in this framework may help reveal new markers and tools that could eventually help inform a surgeon’s expectations and approaches to these patients.”

The study was published in the journal Epilepsia in April 2022.

O’Hara says there’s still much to understand about how epileptic spasms spread through different adolescent brains. The ultimate goal is to make such imaging techniques commonplace so more physicians can better contextualize epileptic spasms and determine which patients are the best candidates for surgery.

Author: Kristy Case, web editor/writer, Graduate School