The truth about the ‘bra-burners’

The 1968 Miss America protest in Atlantic City, NJ, is widely considered the birth of the “bra-burners” but organizers say that no bras were burned. Student Grace Moore set out to investigate the myth and the lasting implications for feminism.

How we remember and talk about historical events changes over time—it’s the premise behind a course Grace Moore took for her joint master of arts in public history and library and information science (MAPH/MLIS). The class was presented with a prompt to research a single historical event that has been subject to “memory discourse,” to analyze how that event has been remembered and why it has changed over time.

“The first thing that came to my mind was the second wave of the feminist movement,” Moore said, “particularly the events and media coverage surrounding September 7, 1968.”

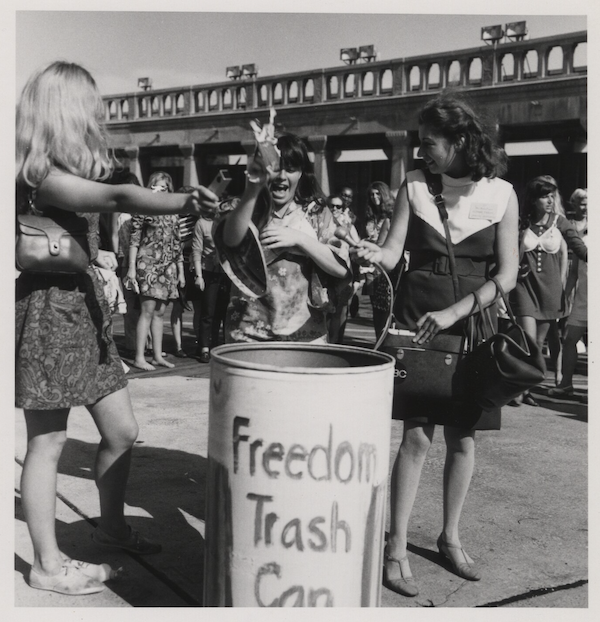

On that day, approximately two hundred feminists and civil rights advocates gathered on the boardwalk in Atlantic City, NJ, to protest the Miss America pageant. The protestors crowned a sheep, auctioned off an effigy of Miss America, and filled a “Freedom Trash Can” with objects of "female torture" such as makeup, ladies’ magazines and feminine clothing, Moore said.

“At the time, Miss America was something that almost everyone watched.”

The demonstration, organized by the radical Women’s Liberation Movement, made global headlines and membership of the radical division of the feminist movement sky-rocketed. More than 50 years later, the protest still holds resonance but what stands out is the birth of the “bra-burning feminist.”

The epithet can be traced back to that protest, though organizers such as Robin Morgan note that not a single bra was burned that day on the boardwalk. The root of the myth and its lasting implications are what Moore set out to investigate.

Done with the best intentions

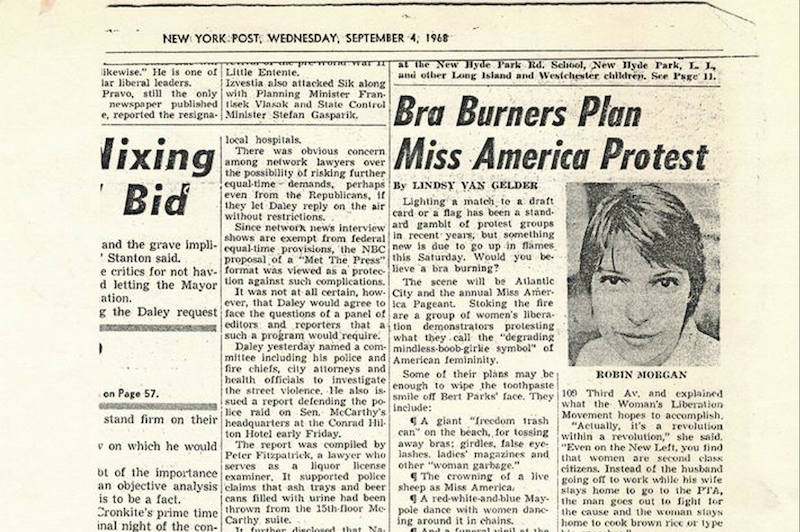

It all started with one well-meaning journalist and an article published in the New York Post three days before the protest.

The organizers said they would only talk to female reporters, Moore said. Lindsy Van Gelder was enlisted by her editors to cover the demonstration.

“They thought it was a joke,” Moore said. “They wanted a frothy and titillating article about women with big ideas about their place in the world.”

Van Gelder was faced with a dilemma: she wanted to get the word out about the protest but knew she had to appease her editors, or they wouldn’t publish, Moore said. Van Gelder tried to compromise with her opening line: “Lighting a match to a draft card or a flag has been a standard gambit of protest groups in recent years, but something new is due to go up in flames this Saturday. Would you believe a bra burning?”

Her editors loved it, Moore said. The New York Post published the piece under a headline not approved by Van Gelder: “Bra Burners Plan Miss America Protest.”

The rest is unintended history.

The headline garnered global attention. It evoked a powerful image for many women but a sexy one that undermined the very points the protesters had set out to make for others, Moore said.

The press used it to vilify the protestors and trivialize women’s concerns.

The New York Post published an article in response to the protest on September 12, 1968, and this time, they did not choose Lindsy Van Gelder but satirist Art Buchwald who painted a vivid picture of women undressing on the boardwalk to “destroy everything this country holds dear.”

It’s a sentiment that many Americans shared then and a sentiment that has endured, Moore said.

Efforts to deny that bras were burned on September 7, 1968, have not been successful; bra-burning has remained tied to feminism in public memory. It’s a caricature that has cropped up in popular media time again.

Moore used the example of the U.S. history teacher Beth Kreydatus who encountered so many students in her own classroom over the years who referred to second-wave feminists as “bra-burners” that in 2008 she wrote an article about it, encouraging other teachers to begin their lectures about the movement by first clarifying the events of the Miss America protest.

And in 2015, Indian actress Priyanka Chopra spoke to Refinery29 about her first role in an U.S. television show, Quantico. She expressed pride in the strong female leads but went on to clarify: “I don’t think it’s a bra-burning feminist show where you’re like, we hate men.”

It shows just how far the narrative reaches, Moore said.

Where it all began

To get to the root of the myth, she knew she had to find the article that started it all but couldn’t find it anywhere online. She reached out to the New York Post archives who told her the article never ran.

“I told them, ‘but I have a photo of the front page.’ This feels like a primary source that should not have disappeared.”

She found the photo in a The Cut article on the radical women’s movement in New York. The Redstockings is listed as the source. Moore reached out in hopes of accessing the entire article but due to the pandemic, their microfilm collection cannot currently be accessed.

That’s when she decided to reach out to Lindsey Van Gelder through her personal website. Not really expecting to hear back, she was surprised when Van Gelder enthusiastically responded. To Moore’s disappointment, Van Gelder didn’t have a copy either, but she did offer up what she remembered.

The two exchanged emails for weeks as Moore compiled her sources and wrote the paper on the controversy of the Miss America pageant.

“She had a lot of information for someone who was verifiably there.”

Van Gelder shared another article she wrote in 1992 where she gave herself up as “The Mother of the Myth of the Maidenform Inferno.” (Maidenform is a brand of lingerie.) In it, she reiterates that no bras were burned on the boardwalk on September 7, 1968.

“I never burned my bra in the sixties,” Van Gelder wrote. “But I wish I had.”

Moore finished her paper titled “The Birth of the Bra-Burners” and hopes to send it to a journal over the summer for publication.

In it, she writes that the “bra-burning feminist” will remain in public memory for as long as there is prejudice against women but that feminists can fight back by continuing to do what they have always done: “promoting the truth about what it actually means to be a feminist.”

Written by Kristy Case, Wayne State University Graduate School