Recentering the narrative

Student and Underground Railroad scholar Rochelle Danquah has spent her career exploring antislavery and abolitionist movements in Michigan. For her dissertation, she’s rediscovering a white, radical group that remains marginalized to history.

In her studies on the antislavery movement, early Americanist Rochelle Danquah stumbled upon a religious group of Scottish settlers who came to America in the early 1600s to escape persecution from England.

In schools, children are taught that the Quakers and William Lloyd Garrison are the first white abolitionists to aid freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad. “But before the Quakers and the Garrisonians, there were the Covenanters,” said Danquah, a Ph.D. student in history. Escapees of oppression themselves, the Covenanters came to America harboring antislavery sentiments. “Simply put, they really were one of the earliest documented white immediatists—abolitionists who did not falter and said not only must slavery end now, but all African Americans must be given full rights as citizens. Even if it must come by way of violence.”

It’s these gun-toting “white radicals” that have inspired Danquah’s dissertation.

For years, she has studied Underground Railroad activism. But it wasn’t until a chance encounter at Southfield Reformed Presbyterian Church that she met Rev. James Faris, whose ancestors were abolitionists, and heard about the Covenanters. “That opened the door for me to meet others.”

Travel research grants took her to Duke University, “where most of their records are in regards to their early settlement in America. … The Covenanters first settled in South Carolina, and then as slavery developed a strong foothold on the state, they ran out of SC and began to organize and have churches throughout the Midwest, anywhere as far as Iowa and right in our own backyard here in Michigan.”

She read letters written by pastors announcing slave owners could not be members of their churches. She learned about Geneva College (which was originally in Ohio but moved to Pennsylvania after the Civil War), where faculty and students carried guns to deter slave catchers from stepping foot on campus and hauling fugitives seeking refuge back into slavery. She discovered the lengths Covenanters went through to aid freedom seekers, believing their actions were sanctioned by the Bible, she said.

“I found this one story where a couple had slave catchers coming to their home because they suspected them of harboring fugitives,” Danquah said. “The husband sat facing the front door with a shotgun while the wife prepared all these pots of boiling water should they enter the couple’s home.

“The Covenanters believed African Americans were their brothers and sisters. Period.”

The Reformed Presbytereian Church’s historical records challenge the dominant narrative that the Quakers were the “first white friends” to freedom seekers. “Covenanters were at the table having conversations with the Founding Fathers before they even penned the Constitution,” she said.

So, why is it by and large that experts and lay historians alone have heard their story? During the abolitionist movement up until present day, the Covenanters have never numbered more than 60,000, Danquah said.

“I guess that’s why we have historians like myself who come along and interject a new argument to hopefully change and recenter the narrative.”

Expanding the network

While Danquah always knew she wanted a Ph.D., she was determined to first raise two kids.

“I wanted to be the kind of mother that went to dance recitals and sports activities. … Once they graduated high school, I said: ‘It’s mommy’s turn.’”

Already a prominent Underground Railroad historian in Michigan with memberships at a variety of organizations, she chose Wayne State University to stay close to home and continue the research.

Senate Majority Leader for the Michigan Freedom Trail Commission, Danquah fields calls from people who suspect a particular building or home was a part of the Underground Railroad. She gets them on the right track to start conducting their own research by asking questions: “‘Is it documented that a fugitive stopped there?’ ‘What do you know about the original homeowners?’”

Determining whether a site was truly on the Underground Railroad is an extensive process, she said, but it’s even tougher to get it registered on the National Underground Railroad Network. “You have to have primary sources, only then is the case strong enough to be vetted for the national application.”

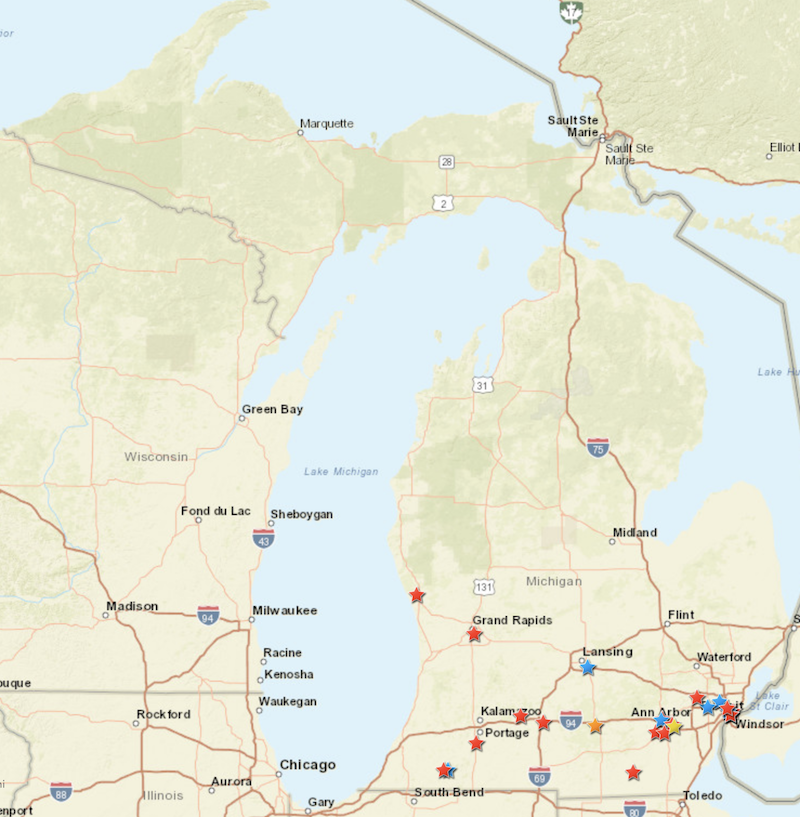

In total, Michigan has 25 sites on the registry. As Detroit shares a border with Canada, it should come as no surprise the city has more “stations” than any other, including the Finny Barn site run by business owner and stationmaster Seymour Finney, the home of abolitionist and freeborn African American George DeBaptiste, and a number of churches—Second Baptist Church located in Greektown the most recently added.

Danquah chairs the Commission’s Sites, Identification, Facilities, and Programs Committee, on which retired teachers, lay historians, historical enthusiasts, and Underground Railroad researchers serve. Every one a volunteer working toward adding sites to the national registry and creating a more holistic picture of antislavery activism in Michigan.

“The first form of resistance and the abolitionist movement in America was of course spurred by the Black community, whether they were enslaved African Americans who self-emancipated or were freedmen and women who were assisting prior to any organized antislavery movement.”

But someone has to tell the Covenanters’ story, too, Danquah said.

“It makes you wonder. If these white radicalized abolitionists were willing to put their lives on the line for the freedom of African Americans in the 19th century, how does that reflect on what’s happening today?”

Danquah’s upcoming speaking engagements:

- Feb. 16, 6:30 p.m. Farmington Genealogical Society. “The Underground Railroad in Farmington, MI.”

- Feb. 24, 7 p.m. Mill Race Historical Village. “Abolitionists in Northville Township.”

- March 19, 3:30 p.m. Michigan in Perspective Conference. “Freedom and Resistance: The Underground Railroad Movement in Southeastern Michigan.”