Parenting in and outside the classroom

Recent alumna Erin Baker puts family first and her research explores the mental health of homeschooling mothers who have made hard decisions to do the same.

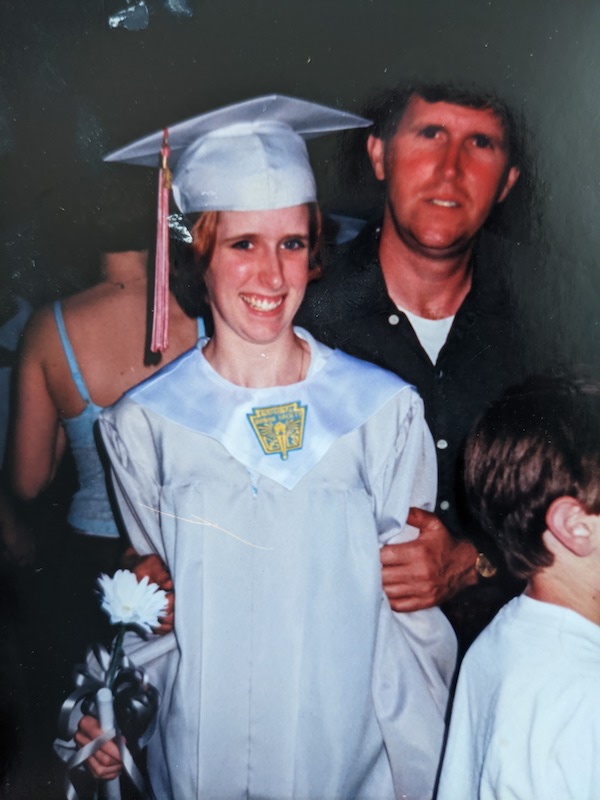

Erin Baker, ‘21 Ph.D., was 10 years old when her father Enoch became an academic services advisor in the Law School and a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at Wayne State University. She spent a lot of time with him over the years roaming the halls before deciding to start her own college experience here. For a year, she and her dad carpooled to campus and met up for lunches until Baker decided to move onto Central Michigan University to complete her undergraduate studies.

Enoch passed away before he could earn his Ph.D. Baker went on to earn a master’s from Eastern Michigan University before setting her sights back on Wayne State for her doctorate in sociology.

“I struggled to find a job and decided to go back.”

It was exciting to return but Baker acknowledged it was hard, too.

“Poor Dr. [Krista] Brumley. When I was first exploring the program, I think I cried in her office three times. It was hard to be there because my dad was gone. I had all those memories.”

She applied to other schools but kept coming back to Wayne State and ultimately enrolled. Before starting school, she and her boyfriend at the time, husband now, “drove around to all the places that I had gone to with my dad to see if we could get all the emotions out,” she said.

And this time, Baker brought her own kid to the hallways of Wayne State. She was a single mom for the first two years of her program before she married and took a lot of night classes. Daycare centers were closed, so she would bring her son to class.

“Everyone was really great to him,” she said. “I don’t think I could have finished [the program] if that had been a problem.”

Reasons parents homeschool

Her dissertation focused on how homeschooling impacts mothers’ mental health. She chose to study homeschooling mothers because, for awhile, she was one.

“My son struggled with the way a traditional classroom is set up—the expectation to sit all day, the expectation to be quiet all the time. He excelled, he was beyond what they were teaching in the classroom, so he was bored.”

By this time, she was married. Baker was a graduate teaching assistant during the day and her husband worked as an audio engineer in the evenings, so they decided to homeschool their son and tag-team the curriculum.

Still, it was a lot of work and incredibly stressful, Baker said. Eager to speak with other women undergoing the same stressors, Baker aimed to launch a national survey for her research at the beginning of 2020. Then, COVID hit.

“I was unable to do half of my study,” she said. “I couldn’t launch the survey because there’s no way to pull out the mental health implications of the pandemic from those caused by homeschooling.”

What she did do was conduct interviews with homeschooling mothers. And it’s no surprise that they were indeed stressed.

The strain primarily resulted from their dual roles, Baker said. Many worked in addition to homeschooling. Others were students themselves, like Baker.

“But they all said, ‘It’s worth it. It’s worth it because my kid’s getting what they need.’”

The majority of homeschooling moms Baker interviewed taught secular curriculums, meaning they weren’t homeschooling their kids for religious reasons. Her study fills a gap in published research on homeschooling that focuses by and large on religious homeschoolers, not parents who homeschool for so many other reasons.

A number of the mothers Baker spoke to chose to homeschool because their child required a unique need their school either refused or lacked the resources to support, she said. These children had autism, attention deficit order, severe allergies, or physical limitations that made a traditional classroom experience difficult, she said.

“They felt stuck. They felt like they didn’t want to be homeschooling but had no other choice.”

Most were relieved to speak to Baker and expressed an eagerness for secular homeschooling and the limitations of traditional schooling to be further explored and publicized.

Future endeavors

Baker graduated with her Ph.D. this summer and at the writing of this article, she and her family are packing their things to move to North Dakota where she starts as a professor at Minot State University in the fall. Currently, her son is enrolled in a virtual academy, but she’s uncertain about schooling plans for the future—with the move to a new state comes new homeschooling laws.

Even though Baker was forced to put her nationwide survey on hold, she still plans to launch it once the pandemic has quieted down. She wants to explore the role fathers play in homeschooling, acknowledging there are dads out there who are the primary educators. She wants to look at homeschooled children with unique needs and the disconnect between what their parents need and what they’re getting and how that gap impacts their mental health.