An anthropology student is telling the stories of Colombians ravaged by war and the drug economy

Andrés Romero grew up in Bogotá, the capital city of Colombia—a nation that has faced decades of civil war paid for in part by the lucrative cocaine demand from abroad. Much of the fighting took place in the countryside, displacing millions—many who were forced into the city and found shelter in Bogotá’s drug-markets controlled by organized crime.

Romero grew up hearing about politics and the drug economy on the news, knowing those he saw on the streets were victims of conflict. He came to the United States at the age of nine, and to his surprise, discovered the States had its own “war on drugs,” which also disproportionally targeted historically marginalized communities. The drug economy wasn’t an issue owned by Colombia alone. The shadow it cast on entire communities stayed with him. His thoughts were never far from home.

Now a Ph.D. candidate studying anthropology at Wayne State University, Romero explores questions of violence, place, memory, and selfhood in Bogotá. The backdrop to his dissertation research is the urbanization of the armed conflict in Colombia, but through a person-centered approach, he focuses on the lives of people displaced into the “ollas” or drug-markets of Bogotá and the state’s attempt at their rehabilitation.

“It’s one thing to gesture toward the political wrongdoings of the state and organized crime,” Romero said. “It’s quite another to think about what that experience is like for people living on the street.”

While the Colombian government and the largest guerilla group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, reached a peace agreement in 2016, evidence shows little has changed in the day-to-day of the people. Violence and social insecurity ensue both in the countryside and in the city.

Shared history

It was in 2016 that Romero returned to Bogotá to conduct ethnographic fieldwork research in the city’s rehabilitation centers, many of which were full of people pulled off the drug-markets in state-sanctioned orders premised on regaining sovereignty and redeveloping downtown.

He said what he witnessed doesn’t fit the typical mold of how most think about rehabilitation. We tend to think of it in terms of “fixing” someone, getting them used to a new normal after their old way of life has been fractured, he said. “But there was nowhere for anyone to be integrated into after rehab, and so people got clean only to be left right back out onto the streets. Rehabilitation was more about deferral, hibernation—waiting for something to arrive.”

Because of the conditions in Colombia, many people ended right back in the drug markets, he said.

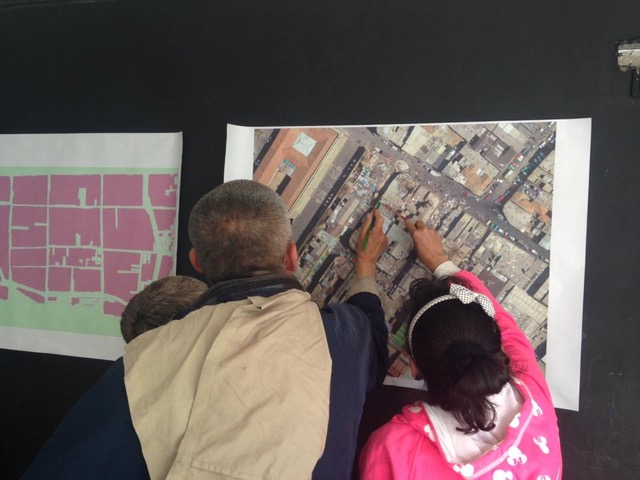

For his dissertation, Romero captures the complexities and collective history of those living in the drug-markets through photography, field note drawings, visual recordings, and oral histories.

“I hope that my research can be engaged as a multi-modal collaborative practice where the aim in qualitative field-based research is not to only document people’s lives and what is happening, but to craft something together with the communities we work with in that process,” he said.

He is already making anthropological knowledge available to the public through the Society for Cultural Anthropology (SCA), a section of the American Anthropological Association. SCA’s film series channel The Screening Room shows independent films for two weeks at a time, and as section editor for their Visual and New Media Review, it’s Romero’s job to create content around the films that can be understood by anyone, both inside and out of academia. He is also currently co-curating a series on experimental media called Con-text-ure.

The big idea behind SCA’s open-access model is that anthropological knowledge doesn’t have to be gatekept by academics, he said. It can be understood and shared by anyone.